- Reference: CS161 | Computer Security

Cryptography

Basics

- Kerckhoff’s Principle is a security principle which states that cryptosystems should remain secure even when the attacker knows all the internal details of the system, except the key.

- Shannon’s maxim is a security principle wherein the enemy knows the system, meaning that you should assume that the attacker knows every detail about the system you are working with. (Don’t rely on security through obscurity)

- Actors

- Alice and Bob: The main characters trying to send messages to each other over an insecure communication channel.

- Carol and Dave can also join the party later

- Eve: An eavesdropper who can read any data sent over the channel (an honest-but-curious attacker).

- Mallory: A manipulator who can read and modify any data sent over the channel (a malicious attacker).

- Alice and Bob: The main characters trying to send messages to each other over an insecure communication channel.

- CIA model

- Confidentiality is a goal of cryptography wherein the adversary cannot read our messages. Essentially, the ciphertext should not give the attacker any additional information about the plaintext.

- experiment: Alice has encrypted and sent one of two messages, either $M_0$ or $M_1$, and the attacker, Eve, has no idea which was sent. Eve tries to guess which was sent by looking at the ciphertext. If the encryption scheme is confidential, then Eve’s probability of guessing which message was sent should be $1/2$.

- This experiment can be applied to different threat models.

- Integrity is a goal of cryptography wherein the adversary cannot change any messages without being detected.

- Authenticity is a goal of cryptography wherein one can prove that a message came from the person who claims to have written it.

- Confidentiality is a goal of cryptography wherein the adversary cannot read our messages. Essentially, the ciphertext should not give the attacker any additional information about the plaintext.

- Symmetric and Asymmetric-Key Cryptography

| property | Symmetric-key | Asymmetric-key |

|---|---|---|

| Confidentiality | Block ciphers with chaining modes (e.g., AES-CBC) | Public-key encryption(e.g., El Gamal, RSA encryption) |

| Integrity and authentication | MACs (e.g., AES-CBC-MAC) | Digital signatures (e.g., RSA signatures). Alice computes a digital signature of her message using her private key, and appends the signature to her message. When Bob receives the message and its signature, he will be able to use Alice’s public key |

| Scheme overview | Alice uses her secret key to encrypt a message, and Bob uses the same secret key to decrypt the message | Alice can encrypt her message under Bob’s public key and Bob will be able to decrypt using his private key. |

-

Threat models

- column 2: can eve trick Alice

- highlight - focus of this course.

- encryption algorithms provide security against chosen-plaintext/ciphertext attacks, both because those attacks are practical in some settings, and because it is in fact feasible to provide good security even against this very powerful attack model.

- replay-attack: eve can send Bob a repeated encrypted message from Alice.

- column 2: can eve trick Alice

-

IND-CPA secure (indistinguishability under chosen plaintext attack): even if Eve can trick Alice into encrypting some messages, she still cannot distinguish whether Alice sent $M_0$ or $M_1$ with probability greater than half.

- if a scheme leaks the plaintext length, it can still be considered IND-CPA secure. (because not leaking length information is impractical)

- Eve is limited to a practical number of encryption requests.

- any algorithm Eve uses during the game must run in $O(n^k)$ time, for some constant $k$.

- Eve only wins if she has a non-negligible advantage.

- Only non-deterministic schemes are IND-CPA secure as nothing is preventing Eve from asking Alice again.

-

One-time pad

- Key generation: Alice and Bob pick a shared random key $K$.

- Encryption $C=M\oplus{K}$

- Decryption $M=C\oplus{K}$

- IND-CPA secure

- The shared key cannot be reused to transmit another message M′, making this infeasible for practical purposes as new keys need to be generated every time.

Block Ciphers

- A block cipher transforms a fixed-length, $n$-bit input into a fixed-length $n$-bit output.

- Encryption function $E:{0,1}^k \times {0,1}^n \rightarrow {0,1}^n$ is a permutation of the $n$-bit input string, given some fixed $k$-bit key. This function is invertible and bijective as it should allow decryption.

- Most common: AES (Advanced Encryption Standard). ($n$ = 128, $k$ = 128). AES is computationally indistinguishable from random. (no proof. but believed to be)

- Block ciphers alone are not IND-CPA secure as they are deterministic.

- To solve this randomization is needed.

| Mode | Encryption | Decryption | Parallelizable | IND-CPA secure |

|---|---|---|---|---|

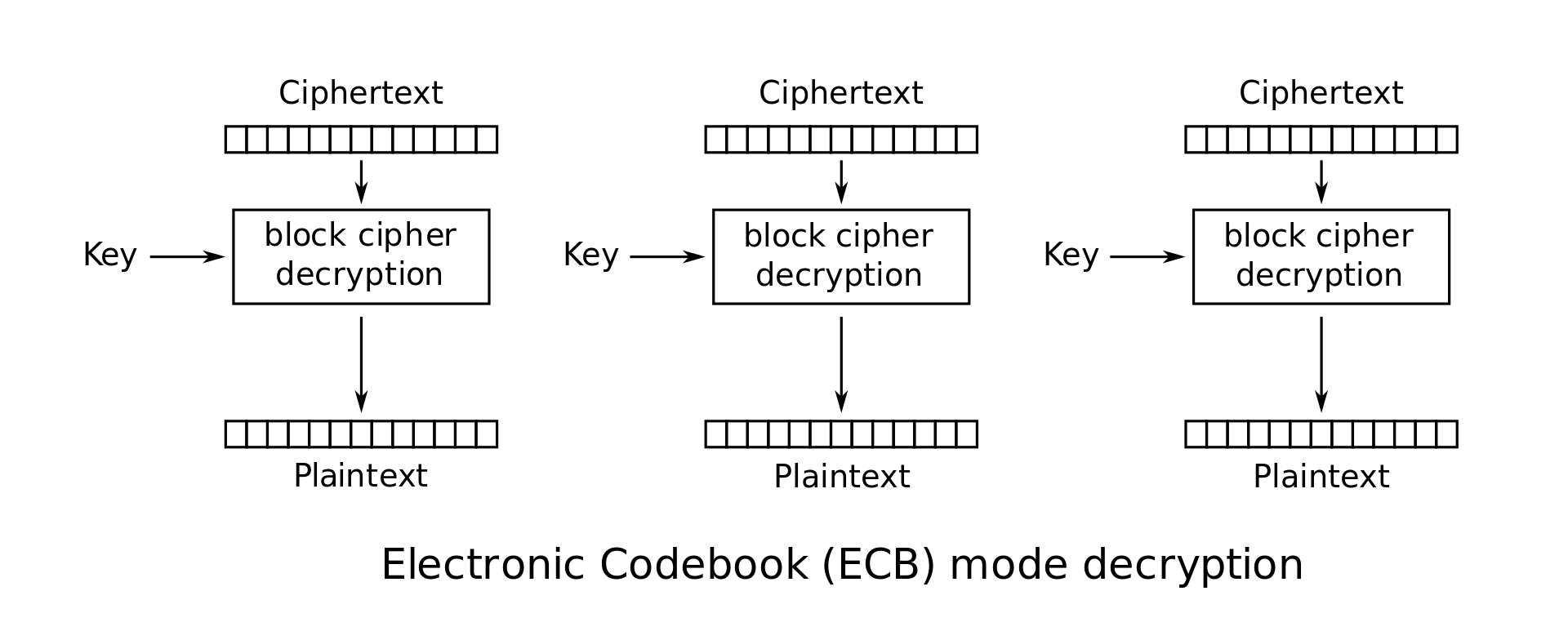

| ECB (electronic code book) | $C_i=E_K(M_i)$ | $M_i=D_K(C_i)$ | Both Encryption and Decrytion | No |

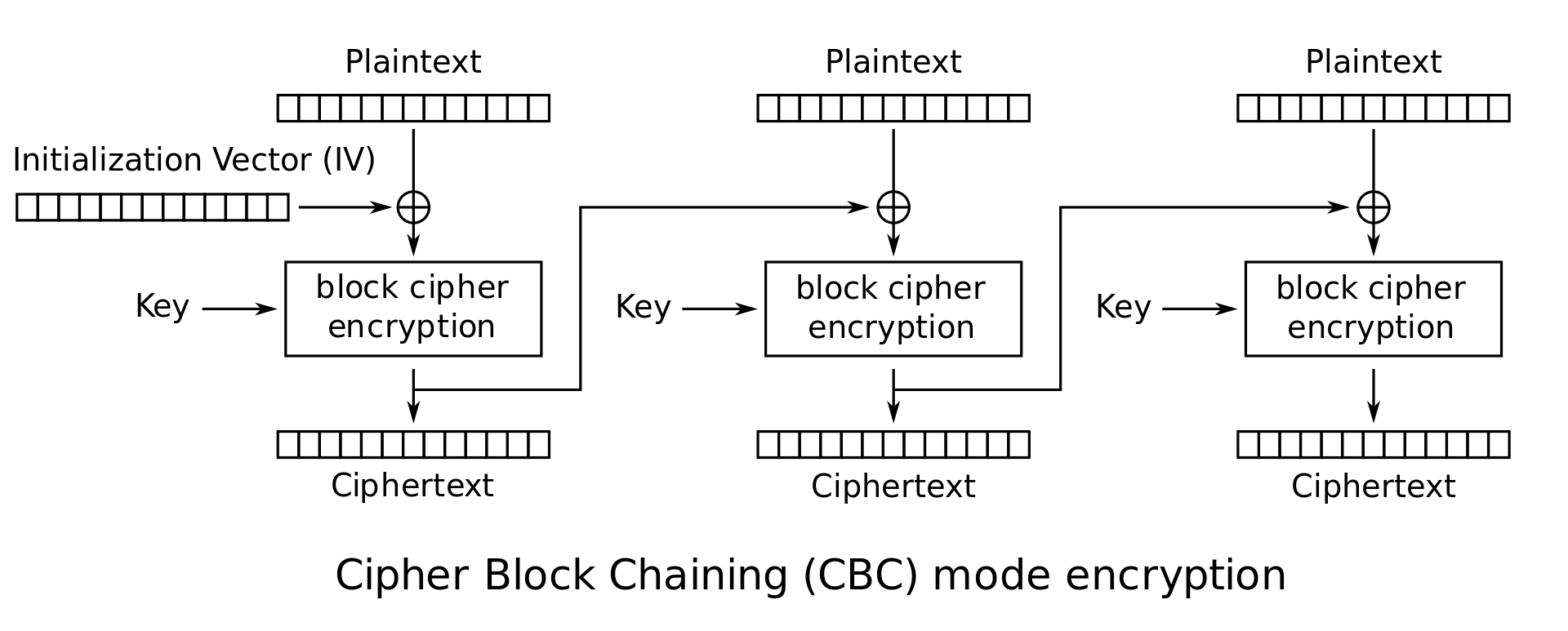

| CBC (cipher block chaining) | $\begin{cases} C_0 = IV \ C_i = E_K(P_i \oplus C_{i-1}) \end{cases}$ | $P_i = D_K(C_i) \oplus C_{i-1}$ | Only Decryption | Yes |

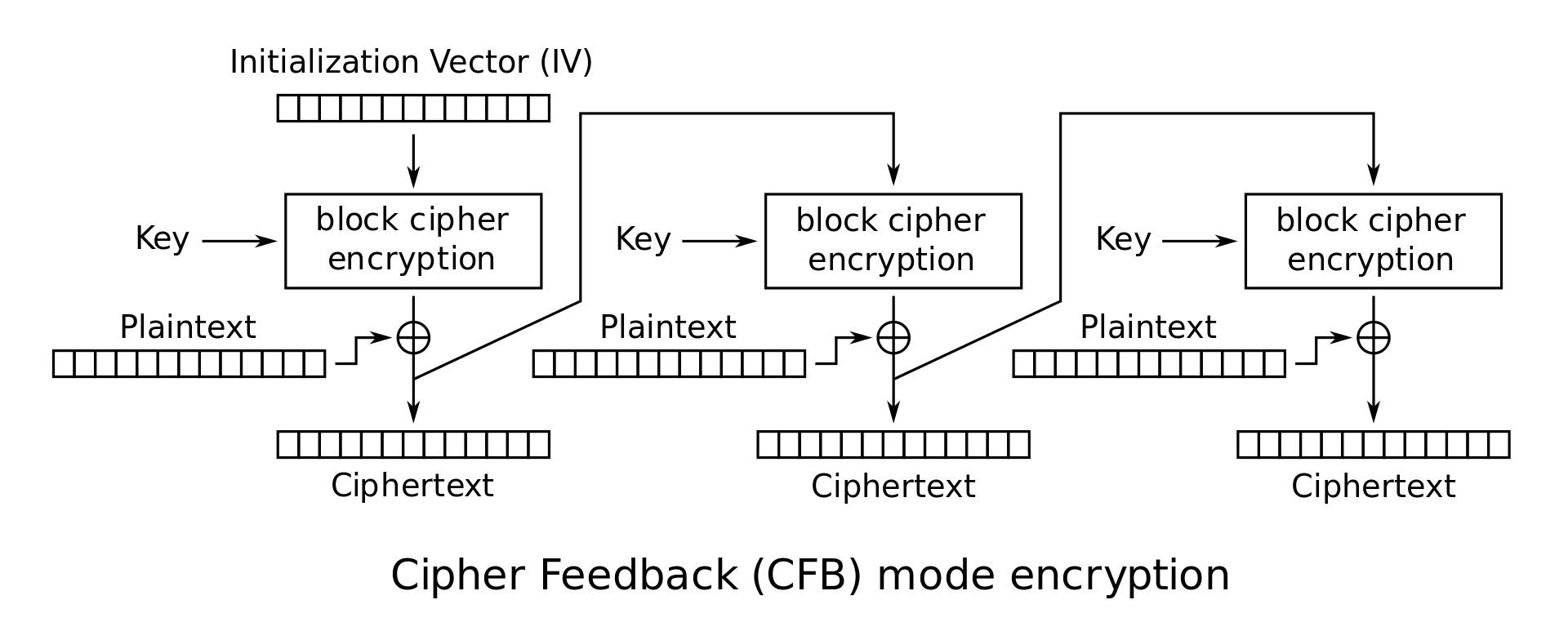

| CFB (ciphertext feedback) | $\begin{cases} C_0 = IV \ C_i = E_K(C_{i-1}) \oplus P_i \end{cases}$ | $P_i = E_K(C_{i-1}) \oplus C_i$ | Only Decryption | Yes |

| OFB (output feedback) | $\begin{cases} Z_0 = IV \ Z_i = E_K(Z_{i-1}) \ C_i = M_i \oplus Z_i \end{cases}$ | $P_i = C_i \oplus Z_i$ | Only Decryption | Yes |

| CTR (counter) | $C_i = E_K(IV + i) \oplus M_i$ | $M_i = E_K(IV + i) \oplus C_i$ | Both Encryption and Decryption | Yes. $IV$ loss catastrophic |

- ECB(electronic code book) mode

- plaintext $M$ is simply broken into $n$-bit blocks $M_1 \dots M_l$,

- Encryption: $C_i=E_K(M_i)$

- Decryption $M_i=D_K(C_i)$

- flawed as it leaks information. (if $M_i=M_j$ then $C_i=C_j$)

- CBC(cipher block chaining) mode

- $IV$ : random $n$-bit string called initialization vector, new for every message (to be used only once), public. (also called nonce - number used once)

- Encryption: $\begin{cases} C_0 = IV \ C_i = E_K(P_i \oplus C_{i-1}) \end{cases}$ (Cannot be parallelized)

- Decryption: $P_i = D_K(C_i) \oplus C_{i-1}$ (Can be parallelized)

- strong security guarantees

- CFB Mode (Ciphertext Feedback Mode)

- Encryption: $\begin{cases} C_0 = IV \ C_i = E_K(C_{i-1}) \oplus P_i \end{cases}$

- Decryption: $P_i = E_K(C_{i-1}) \oplus C_i$

- OFB Mode (Output Feedback Mode)

- Encryption: $\begin{cases} Z_0 = IV \ Z_i = E_K(Z_{i-1}) \ C_i = M_i \oplus Z_i \end{cases}$

- Decryption: $P_i = C_i \oplus Z_i$

- Counter (CTR) Mode

- Encryption: $C_i = E_K(IV + i) \oplus M_i$

- Decryption: $M_i = E_K(IV + i) \oplus C_i$

- Note that all the above schemes can be tampered by simply swapping different ciphertext blocks, thus providing Confidentiality but not Integrity and Authenticity.

- Padding

- Used when message isn’t multiple of block size.

- Padding scheme

PKCS#7: pad the message by the number of padding bytes used. - Used in CBC (cipher block chaining) mode but not in CTR (counter) mode. See the decryption function to decide.

Cryotographic Hashes

- One Way: $y=H(x)$. Not possible to find $x$ s.t $H(x)=y$ for a given $y$.

- Second preimage resistant: infeasible to find another input $x’$ such that $x’ \neq x$ but $H(x)=H(x’)$.

- Collision resistant: infeasible to find any pair of messages $x,x’$ such that $x \neq x’$ but $H(x)=H(x’)$. (practically infeasible)

- Example use case: If publicised hash is authentic, then we can compare the publicised hash with the downloaded software/file’s hash to check if it hasn’t been tampered with.

- Algorithms

- MD5, SHA-1: broken

- SHA-2 (vulnerable to length extension attack), SHA-3: in use

- selection: relate output length to corresponding symmetric key algorithm. For AES-128, use SHA-256 or SHA-384, making cracking equally difficult

Message Authentication Codes (MACs)

- The MAC on a message $M$ is a value $F(K,M)$ computed from $K$ and $M$; the value $F(K,M)$ is called the tag for $M$ or the MAC of $M$. Typically, we might use a 128-bit key $K$ and 128-bit tags.

- While sending a message send $\langle M,T \rangle$.

- To check integrity and authenticity, compute the MAC of the message part and compare with the Tag.

- Deterministic as it is used for comparing.

- Does not guarantee confidentiality. Only Authenticity and Integrity

- No eve should be able to generate valid MAC for unseen messages.

- MACs provide security against chosen-plaintext/ciphertext attacks.

- AES-EMAC

- $K=\langle K_1, K_2 \rangle$

- $M = P_1 \Vert P_2 \Vert … \Vert P_n$

- $S_0=0$, $S_i=AES_{K_1}(S*i-1 \oplus P_i)$

- $T=AES_{K_2}(S_n)$

- provably secure assuming AES is secure.

- HMAC (Hash Message Authentication Code)

- when using with a block cipher, choose an HMAC whose output is $2 \times key$ length used for the associated block cipher.

- output of HMAC is the same number of bits as the underlying hash function

- $\text{NMAC}(K_1, K_2, M) = H(K_1 \Vert H(K_2 \Vert M))$

- HMAC(uses only 1 key) is a more specific version of NMAC

- Authenticated encryption

- encrypt-then-MAC

- $\langle \mathsf{Enc}{K_1}(M), \mathsf{MAC}{K_2}(\mathsf{Enc}_{K_1}(M))\rangle$

- better approach.

- MAC-then-encrypt approach

- $\mathsf{Enc}{K_1}(M \Vert \mathsf{MAC}{K_2}(M))$

- only detect if the message is tampered after we decrypt it.

- encrypt-then-MAC

Pseudorandom Number Generators

- Seed(entropy): Take in some initial truly random entropy and initialize the pRNGs internal state.

- Reseed(entropy): Take in some additional truly random entropy, updating the pRNGs internal state as needed.

- Generate(n): Generate $n$ pseudorandom bits, updating the internal state as needed. Some pRNGs also support adding additional entropy directly during this step.

- rollback resistance: previously-generated output of the pRNG should still be computationally indistinguishable from random, even if the attacker knows the current internal state of the pRNG.

- HMAC-DRBG

- computes HMAC on the previous block of pRNG output. repeats.

- internal state: $K$ and $V$ (message part of HMAC). update after generation of $n$ bits.

- Additional true randomness can also be provided.

- Stream-Cipher

- encrypt a stream of bytes coming (Ex. movie)

- Use one time pad for encryption and decryption of every bit.

- bits generated using pRNG

- Secret key is used to seed the pRNG

- use an additional $IV$ to seed.

- Encryption: $Enc(K, M) = \langle IV, PRNG(K, IV) \oplus M \rangle$

- Decryption: $Dec(K, IV, C_2) = PRNG(K, IV) \oplus C_2$

- Use of counter in stream cipher: ability to encrypt or decrypt an arbitrary point in the message without starting from the beginning

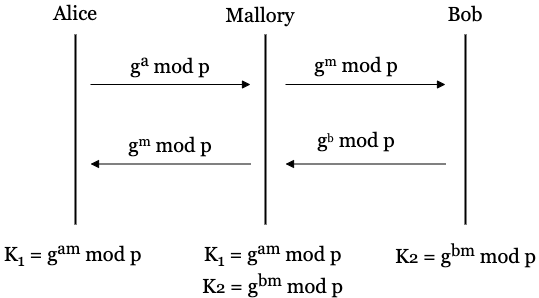

Diffie-Hellman Key Exchange

- Remember the paint exchange analogy. One public paint colour is known. Alice and Bob exchange public paint mixed with their own secret colours and then add their own colour to the received mix to generate the common secret key.

- One way function

- $f$ s.t given $x$, it is easy to compute $f(x)$, but given $y$, it is practically impossible to find a value $x$ s.t $f(x)=y$

- Ex. $f(x) = g^x \bmod p$. ($p$ is a large prime and $1<g<p-1$)

- discrete logarithm problem: computationally hard to solve

- $g$, $p$ are fixed and public

- $A = g^a \bmod p$

- $B = g^b \bmod p$. ($a$, $b$ $\in {0,1,\dots,p-2}$)

- $S = B^a = A^b = g^{ab} = g^{ba} \bmod p$. $S$ is the shared secret.

- Elliptic curve Diffie-Hellman: smaller keys with same security

- Protocol only resistant against Eve but not Mallory.

- Happens due to lack of integrity and authenticity.

Public Key Encryption

- Public-key cryptography provides a nice way to help with the key management problem. Alice can pick a secret key $K$ for some symmetric-key cryptosystem, then encrypt $K$ under Bob’s public key and send Bob the resulting ciphertext. Bob can decrypt using his private key and recover $K$. Then Alice and Bob can communicate using a symmetric-key cryptosystem, with $K$ as their shared key, from there on.

- trapdoor one-way function: same as a one-way function, but given $y$ and a special backdoor $K$, it is easy to find an $x$ s.t $f(x)=y$.

- given a private key $PK$ and a ciphertext $y$, it is easy for find $x=f^{-1}(y)$.

- El Gamal encryption:

- System parameters: a 2048-bit prime $p$, and a value $g$ in the range $2 \ \dots p − 2$. Both are arbitrary, fixed, and public.

- Key generation: Bob picks $b$ in the range $0 \dots p − 2$ randomly, and computes $B = g^b \bmod p$. His public key is $B$ and his private key is $b$.

- Encryption: $E_B(m) = (g^r \bmod p, m \times B^r \bmod p)$ where $r$ (Alice’s private key) is chosen randomly from $0 \dots p − 2$, let $R = g^r \bmod p$.

- Decryption: $D_b(R,S) = R^{−b} \times S \bmod p$.

- RSA encryption:

- Key generation:

- $p, q$ random 2 large primes.

- $N=pq$

- let $e$ (usually 3, 17, 65, 537) be such that $gcd(e, (p - 1)(q - 1)) = 1$

- Public Key: $(N, e)$

- Private Key: $d = e^{-1} \bmod (p-1)(q-1)$

- Enc(e, N, M): $C = M^e \bmod N$

- Dec(d, C): $C^d \bmod N$.

- Key generation:

- RSA isn’t IND-CPA secure (because deterministic).

- to counter this, OAEP (Optimal Asymmetric Encryption Padding) is used.

- RSA uses two variables during encryption while El Gamal uses three variables

- Public key cryptography relies on the fact that the published public key really belongs to the person it is supposed to. Is the public key integrity maintained?

- Session keys: because public key cryptography is computationally expensive, we use it to distribute session keys. These keys are symmetric keys used for various purposes - encrypting messages and in MACs.

Digital Signatures

- Needed for non repudiation

- In case of symmetric keys, we cannot prove who generated the message.

- Asymmetric algorithms

- On its own doesn’t provide confidentiality

- Use private key while signing

- Key generation: There is a randomized algorithm $KeyGen$ that outputs a matching public key and private key: $(PK,SK) = KeyGen()$ . Each invocation of $KeyGen$ produces a new keypair.

- Signing: There is a signing algorithm Sign: $S = Sign(SK,M)$ is the signature on the message $M$ (with private key $SK$).

- Verification: There is a verification algorithm $Verify$, where $Verify(PK,M,S)$ returns true if $S$ is a valid signature on $M$ (with public key $PK$) or false if not.

- RSA Signatures: $H(M) = F_U(S)$. $S$ is the signature, $H$ is the hash function. $F$ is a trapdoor one-way function, $U$ - public key.

- The signer computes $S = F^{-1}(H(M))$ as he has the private key $K$

- Because $H$ is one way and $F$’s trapdoor is not known to the attacker, the message cannot be decrypted by an attacker.

- Hash allows signing large messages.

- digital envelop

- message + signature is visible. used for confidentiality. uses symmetric keys too.

Digital certificates

- how do we know that the public key is authentic as claimed by the person?

- MITM attack on public keys

- Digital certificates are a way to represent an alleged association between a person’s name and their public key, as attested by some certifying party.

- The certifying party signs a message with the name and public key of the person with its own private key.

- For Alice to communicate with Bob, she needs to trust the certifying authority and have its trusted correct public key to decrypt the message and obtain Bob’s public key.

- The public key of the trusted CA can be hardcoded in applications that need to use cryptography.

- Web browsers come configured with a list of many trusted CAs.

- certificate chain: a sequence of certificates, each of which authenticates the public key of the party who has signed the next certificate in the chain.

- Revocation: CA can issue certificates with validity periods and additionally list invalid certificates through revocation lists.

- Risk: DoS attack on the revocation list servers.

- roughly 150 root CAs

Bitcoin

- The goal of Bitcoin is to replicate these basic properties of a functioning currency system, but without any centralized party. Instead of relying on a trusted entity, Bitcoin uses cryptography to enforce the basic properties of currency.

- Identity: Public key of a user.

- Messages:

- $PK_A$ sends $n$ units of currency to $PK_B$

- anyone can confirm this

- Balances

- Trusted ledger

- A ledger is a written record that everybody can view

- append only, immutable

- distributed

- Trusted ledger

- Hash chains

- if you get the hash of the latest block from a trusted source, then you can verify that all of the previous history is correct

| Block 1 | Block 2 | Block 3 | Block 4 | Block 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| $m_1$ | $m_2, H(\text{Block}_1)$ | $m_3, H(\text{Block}_2)$ | $m_4, H(\text{Block}_3)$ | $m_5, H(\text{Block}_4)$ |

- consensus

- every participant in the network stores the entire blockchain (and thus all of its history) since we don’t utilize a centralized server.

- new transaction, is broadcast to everyone, and verified by all. If the transaction is correct, everyone will append it to their local blockchain.

- assumption - majority of the users are honest (more than half)

- Consensus via proof of work

- miners - can only add a block if they have a valid proof of work

- a computational puzzle that takes the hash of the current block concatenated with a random number. This random number can be incremented so that the hash changes, until the proof of work is solved.

- Miners then broadcast blocks with their proof of work. All honest miners listen for such blocks, check the blocks for correctness, and accept the longest correct chain.

- By always accepting the longest blockchain, all the miners are ensured to have the same blockchain view.

- Sybil attack

- small number of users counterfeiting multiple peer identities so as to compromise a disproportionate share of the system.

- Majority is defined by computational power.

Network Security

Introduction to Networking

- A group of local machines forms a local area network (LAN).

- all machines are connected to all other machines

- A router is used to connect multiple LANs.

- wide area network forms the basis of the Internet.

- Layers

- Layer 1: Communication of bits

- Layer 2: Local frame delivery

- Ethernet: The most common Layer 2 protocol

- MAC addresses: 6-byte addressing system used by Ethernet

- Layer 3: Global packet delivery

- IP: The universal Layer 3 protocol

- IP addresses: 4-byte (32 bit) addressing system used by IP

- Layer 4: Transport of data

- Layer 7: Applications and services (the web)

- Each layer has its own set of protocols

- To support protocols, messages are sent with a header

- Each layer adds its own header to the top of the message provided from the layer directly above.

- When the message reaches the lowest layer from the top, it now has multiple headers, starting with the header for the lowest layer first.

- At destination, starting at the lowest layer, the message moves up the protocol stack to higher layers. Each layer removes its header and provides the remaining content to the layer directly above. When the message reaches the highest layer, all headers have been processed, and the recipient sees the regular human-readable text from before.

- Layer 2 (link layer) uses 48-bit (6-byte) MAC addresses to uniquely identify each machine on the LAN.

- written as 6 pairs of hex numbers

- the broadcast address of

ff:ff:ff:ff:ff:ff - CSMA/CD protocol - carrier sense multiple access collision detection

- Layer 3 (IP layer) uses 32-bit (4-byte) IP addresses

- IPv6, uses 128-bit IP addresses, which are written as 8 2-byte hex values separated by colons, such as

cafe:f00d:d00d:1401:2414:1248:1281:8712

- IPv6, uses 128-bit IP addresses, which are written as 8 2-byte hex values separated by colons, such as

- higher layers (transport layer) assign each process on a machine a unique 16-bit port number

- web servers HTTP requests - port 80

- HTTPS - port 443.

- Ports below 1024 - “reserved”

- At the lower layers, we call individual messages packets. Packets are usually limited to a fixed length.

- The IP (Internet Protocol) at layer 3 only guarantees best-effort delivery, and does not handle any errors. Instead, we rely on higher layers for correctness and security.

- Adversaries

- Off-path Adversary: The off-path adversary cannot read or modify any messages over the connection.

- On-path Adversary: The on-path adversary can read, but not modify messages.

- In-path Adversary: The in-path (man-in-the-middle) adversary has all the powers of the on-path adversary and can additionally modify and block messages sent by either party.

ARP

- Layer: Link (2)

- Purpose: Translate IP addresses to MAC addresses

- Vulnerability: On-path attackers can see requests and send spoofed malicious responses

- Defense: Switches,

arpwatch - ARP, the Address Resolution Protocol, translates Layer 3 IP addresses into Layer 2 MAC addresses. ARP replies are always cached

- three steps:

- Alice would broadcast to everyone else on the LAN: “What is the MAC address of

1.1.1.1?” - Bob responds by sending a message only to Alice: “My IP is

1.1.1.1and my MAC address isca:fe:f0:0d:be:ef.” Everyone else does nothing. - Alice caches the IP address to MAC address mapping for Bob.

- Alice would broadcast to everyone else on the LAN: “What is the MAC address of

- ARP Spoofing:

- no way to verify that the reply in step 2 is actually from Bob

- Mallory is able to create a spoofed reply and send it to Alice before Bob can send his legitimate reply

- Defense:

arpwatch- tracks the IP address to MAC address pairings across the LAN and makes sure nothing suspicious happens.- Switches: VLAN

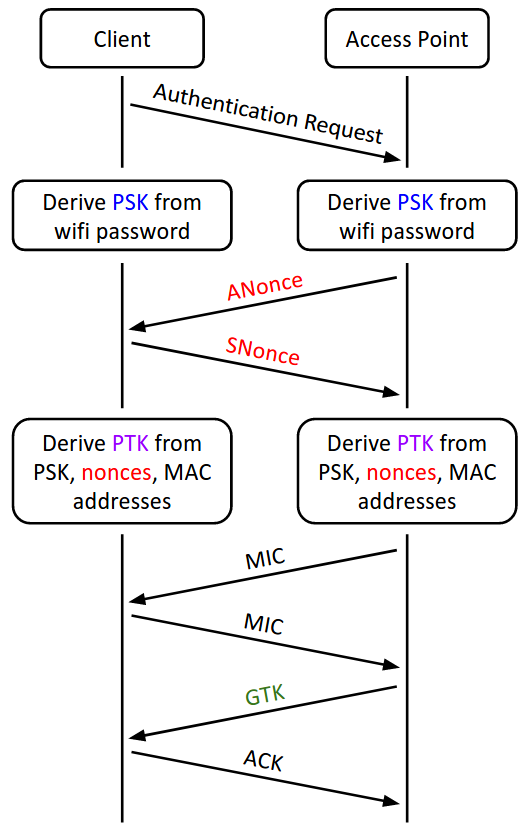

WPA

- WPA2-PSK (WiFi Protected Access: Pre-Shared Key) is a protocol that enables secure communications over a WiFi network by encrypting messages with cryptography.

- Layer: Link (2)

- Purpose: Communicate securely in a wireless local network

- Vulnerability: On-path attackers can learn the encryption keys from the handshake and decrypt messages (includes brute-forcing the password if they don’t know it already)

- Defense: WPA2-Enterprise

- WPA2-Enterprise gives authorized users a unique username and password

- the authentication server presents both the client and the access point with a random PMK (Pairwise Master Key) to use instead of the PSK

- all further communication between the client and the access point is encrypted with the PTK

- The GTK is used for messages broadcast to the entire network (i.e. sent to the broadcast MAC address,

ff:ff:ff:ff:ff:ff). The GTK is the same for everyone on the network, so everyone can encrypt/send and decrypt/receive broadcast messages. - In practice, the handshake is optimized into a 4-way handshake, requiring only 4 messages to be exchanged between the client and the access point.

DHCP

- DHCP (Dynamic Host Configuration Protocol) is responsible for setting up configurations when a computer first joins a local network

- Steps:

- Client Discover: The client broadcasts a request for a configuration.

- Server Offer: Any server able to offer IP addresses responds with some configuration settings. (In practice, usually only one server replies here.)

- Client Request: The client broadcasts which configuration it has chosen.

- Server Acknowledge: The chosen server confirms that its configuration has been chosen.

- Vulnerability: On-path attackers can see requests and send spoofed malicious responses

- Defense: Accept as a fact of life and rely on higher layers

BGP

- Layer: 3 (inter-network)

- Purpose: Send messages globally by connecting lots of local networks

- Vulnerability: Malicious local networks can read messages in intermediate transit and forward them to the wrong place

- Defense: Accept as a fact of life and rely on higher layers

TCP and UDP

- The UDP and TCP header contains 16-bit source and destination port numbers to support communication between processes. The header also contains a checksum (non-cryptographic) to detect corrupted packets. Both protocols are stateless.

- TCP connection is identified by a 5-tuple of

(Client IP Address, Client Port, Server IP Address, Server Port, Protocol=TCP).- No Confidentiality or Integrity by itself

| Sequence number (SYN) | Acknowldgement number (ACK) |

|---|---|

| 32 bit | 32 bit |

| index of the first byte sent | index of the last byte received, plus 1. Ex: in packets from the client to the server, the ACK number is the next unsent byte in the server-to-client stream, and in packets from the server to the client, the ACK number is the next unsent byte in the client-to-server stream |

| reconstruct the message in the correct order | after a timeout period, the sender will re-send that packet |

| Each TCP packet can contain both data and an acknowledgment that a previous packet was received |

- To end a connection, one side sends a FIN (a packet with the FIN flag set), and the other side replies with a FIN-ACK.

- Side that sent the FIN will not send any more data, but can continue accepting data.

- RST packet

- unilateral abortion

- no more packets accepted or sent

- no acknowledgment

- Attacks

- RST injection: abruptly end connection

- Different network attackers attack differently

- Off path - needs to guess initial sequence number

- On path - needs to race an own packet against sender to receiver

- In path - can block, modify, do anything without racing

TLS

- TLS (Transport Layer Security) is a protocol that provides an end-to-end encrypted communication channel. (SSL - old version)

- End-to-end encryption - no person other than sender and receiver can read or modify data.

- layer 6.5 protocol

- Uses the underlying TCP.

- Client sends $R_B$ and a list of encryption protocols it supports.

- Server responds with $R_S$ and the certificate signed by CA

- Next is to generate a premature secret (PS)

- generate random and encrypt with RSA

- Or, use Diffie Hellman

- Generating the PS with DHE and ECDHE (elliptic curve DHE) has a substantial advantage over RSA key exchange, because it provides forward secrecy

- Suppose an attacker records lots of RSA-based TLS communications, and some time in the future manages to steal the server’s private key. Now the attacker can decrypt PS values sent in old connections, which violates the security of those old TLS connections.

- Use the PS and the random values $R_B$ and $R_S$ to derive a set of four shared symmetric keys: an encryption key $C_B$ and an integrity key $I_B$ for the client, and an encryption key $C_S$ and an integrity key $I_S$ for the server.

- client and server exchange and verify MACs over all messages sent so far

- $I_B$ and $I_S$ are known to both the client and server so that they can verify.

- Security against replay attacks:

- For a connection: due to randomly generated $R_B$ and $R_S$.

- For the same connection: counter or timestamp so that an attacker cannot record a TLS message and send it again within the same connection.

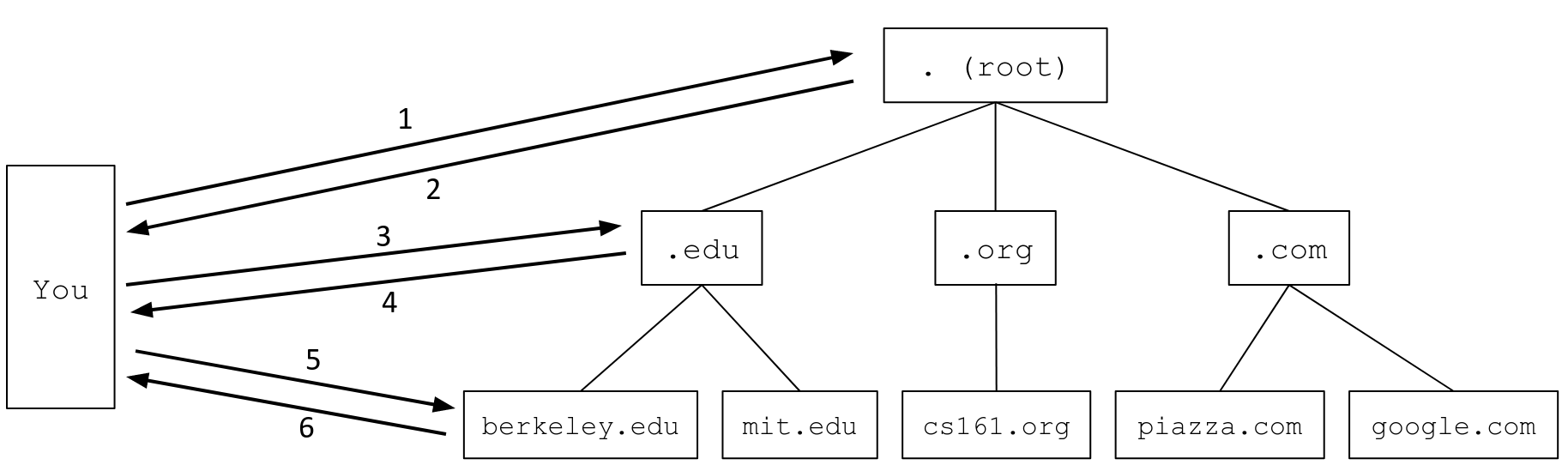

DNS

- A DNS query for

eecs.berkeley.edu

- uses UDP

- 13 root servers

- Each name server is only responsible for storing information about their children, except for the name servers at the bottom of the tree, which are responsible for storing the actual mappings from domain names to IP addresses.

- A DNS Recursive Resolver provided by your Internet service provider (ISP), which sends the queries, processes the responses, and maintains an internal cache of records. When performing a lookup, the DNS Stub Resolver on your computer sends a query to the recursive resolver, lets it do all the work, and receives the response.

| 16 bits | 16 bits |

|---|---|

| Identification (used to match requests to responses) | Flags (NOERROR, NXDOMAIN) |

| # Questions (=1) | # Answer RRs (Resource records) |

| # Authority RRs | # Additional RRs |

| Questions (variable # of RRs) | |

| Answers (variable # of RRs) | |

| Authority (variable # of RRs) | |

| Additional info (variable # of RRs) |

- A DNS record key is formally defined as a 3-tuple

<Name, Class, Type> - A DNS record value contains

<TTL, Value>- A type records map domains to IP addresses (

AAAAfor IPv6) - NS type records map zones to domains

- number of additional records is always 1 more than the actual number of additional records that appear in the response (extra record corresponds to the

OPTpseudosection)

- A type records map domains to IP addresses (

|

|

- With bailiwick checking, a name server is only allowed to provide records in its zone. (Ex. a

.comNS can’t provide for.edu) - The Kaminsky attack relies on querying for nonexistent domains.

- include malicious additional records in the fake DNS response and make the victim query nonexistent domains.

- There is no way to completely eliminate the Kaminsky attack in regular DNS, although modern DNS protocols add UDP source port randomization to make it much harder. (This doesn’t stop On path attackers)

DNSSEC

- DNSSEC is an extension to regular DNS that provides integrity and authentication on all DNS messages sent

- Issue: What if name server is malicious?

- Have a trust anchor: The root servers

- Each name server will sign the public key of all its trusted children name servers, starting from the root

- The

DNSKEYtype record encodes a public key. - The

RRSIGtype record is a signature on a set of multiple other records in the message, all of the same type. - The

DS(Delegated Signer) type record is a hash of the signer’s name and a child’s public key.

| KSK (Key Signing Key) | ZSK (Zone Signing Key) |

|---|---|

| used to sign ZSK | used to sign everything else |

| endorsed by the parent | resolver verifies by using public ZSK |

- DNSSEC sign records offline–records

- In case of nonexistent records, name servers pre-compute signatures on ranges of nonexistent domains.

- NSEC record - no domains exist between domains.

NSEC3,NSEC5- newer versions, uses hash instead of domain names

- NSEC record - no domains exist between domains.

DoS

- Any attack that is designed to cause a machine or a piece of software to be unavailable and unable to perform its basic functionality is known as a denial of service (DoS) attack.

- Attackers can generate a unique source IP address for every packet sent, thus preventing the target from successfully identifying and blocking the attacker.

- Application level

- exhausting the RAM by having continuous calls to

malloc - exhausting the processing threads by having continuous calls to

fork - exhausting the disk I/O operations

- Prevention: Identification, Isolation, Quotas (proof-of-work : like a CAPTCHA)

- exhausting the RAM by having continuous calls to

- In a SYN flooding attack

- send a large number of SYN packets to the server

- ignore the SYN/ACK replies

- never send the ACK response

- mitigation: SYN cookies - Only when the handshake is complete will the server allocate state for the connection after checking the cookie against the secret.

- Often, attackers carry out DDoS attacks by using botnets, a series of large networks of machines that have been compromised and are controllable remotely.

- no way to completely eliminate

Firewall

- Turn off every unnecessary network service

- Firewalls reduce risk by blocking network outsiders from having unwanted access to all the network services by acting as a choke point between the internet (outsiders) and your internal network.

- An inbound connection is one that is initiated by external users and attempts to connect to services that are running on internal machines.

- an outbound connection is one which is initiated by an internal user, and attempts to initiate contact with external services.

- Security policy: A kind of access control policy

- Subjects - computers

- Objects - network services

- Policy - whether that subject has permission to access that object

- Two ways

- Default-allow or blacklist: By default, every network service is permitted unless it has been specifically listed as denied.

- Default-deny or whitelist: By default, every network service is denied to external users, unless it has been specifically listed as allowed. Much safer bet

- we can identify each network service with a triplet $(m,r,p)$

- $m$ - IP address of a machine

- $r$ - protocol identifier (i.e. TCP or UDP)

- $p$ - port number

- An allow list would include triplets. Ex.

(1.2.3.4, TCP, 80)

|

|

- A stateful packet filter maintains state, meaning that it keeps track of all open connections that have been established.

- Application-layer firewalls restrict traffic according to the content of the data fields. These types of firewalls have certain security advantages since they can enforce more restrictive security policies and can transform data on the fly.

- Ex. Proxy servers. all traffic goes through them.

- Firewalls also embody orthogonal security meaning that it can be deployed to protect pre-existing legacy systems much more easily than other security mechanisms that have to be integrated with the rest of the system.

IP security

- IP spoofing countermeasures

- TCP handles it with sequence numbers.

- Ingress filtering - block outside network packets having inside network address.

- Egress filtering - block outgoing packets with non matching destination network addresses.

- ICMP - internet control message protocol

- helps IP in error reporting

- simple queries (

ping)

- IPSec

- layer 3.5

- CIA in this layer.

- modifications in OS

- connection oriented i.e has state (contrary to IP)

- IP packet can be changed in a MITM attack as routers have access to the packet.

- If IP security is handled, then all layers above are secure.

- use cases - VPNs

- Send packets by Symmetric key encryption.

- SA (security association) = SPI + Destination IP + IPSec (ESP pr AH)

- SPD (security policy database) - used to map outgoing packet to a particular SA

- ESP

- Provides source authentication, data integrity and confidentiality

- transport mode - end to end hosts

- original IP header is visible

- tunnel mode (uses gateway)

- default IPSec mode

- protects the payload and IP header of original packet

- authentication is applied to data in ESP header and data in payload.

- process

- verify sequence number, verify integrity and decrypt

- IKE (internet key exchange)

- for establishing a shared secret for IPSec (SA)

- bidirectional, contrary to the unidirectional SA